By: Helena Alvarez

According to data provided by the World Economic Forum (WEF), El Salvador was the second most economically competitive country in Central America in 2006. It has since re-positioned itself as the third least competitive, earning a rank of 84 out of 144 countries. Although El Salvador strikingly climbed 13 positions from its original 2013-2014 ranking on account of having what the WEF considers good infrastructure- the greatest ascent experienced by any Central American country this past year- an increase in commercial regulations and an escalation of violence have promoted an anti-competitive business climate in the country, which could imperil its economy and performance on the Global Competitiveness Index in years to come.

In the 1990’s and early 2000’s, El Salvador made great strides in liberalizing its market economy. Policy initiatives included the privatization of banks and telecommunication systems, the reduction of import duties and the enforcement of intellectual property rights.

Despite these efforts the Salvadoran government has, in recent years, instituted measures that have arguably deterred foreign companies from “setting up shop” in the country. Companies based in El Salvador are forced to pay one of the highest corporate income tax rates (30 percent) in Central America. This has led many businesses to relocate and take their investments to neighboring countries. It is unsurprising to find then that El Salvador’s net foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow fares significantly low at 275 million USD compared to the regional annual average of 1 billion USD, according to an estimate made by the country’s Central Bank (2014).

The Salvadoran government has also taken other steps to encumber more than just companies trying to invest overseas. In September of 2014, a tax on financial operations entered into force, leaving local banks malcontent. Several years ago, the government also introduced a minimum income tax on net assets, which the country’s Supreme Court of Justice deemed unconstitutional in April of this year on the basis of violating principles of tax fairness and individuals’ ability to pay and generate taxable income.

Jurisdictional insecurity has also played a huge part in driving foreign investment away from El Salvador. The CEL-Enel legal dispute has most recently made this evident. Because the Salvadoran government refused to comply with an award granted by the International Chamber of Commerce that permitted Enel, an Italian power company, to invest 100 million USD in a geothermal joint venture, Enel has, since 2008, been attempting to sue the Salvadoran government. After a long-fought battle over the state’s compliance with the law, it was decided in late 2014 that Enel would sell its shares for 280 million USD and retreat its business operations from El Salvador, like many other foreign companies have done already.

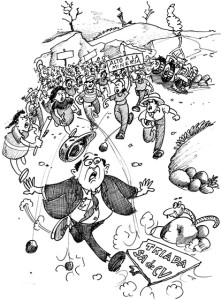

El Salvador’s business climate is, last by not least, threatened by pervasive crime and violence. In May of this year, 635 homicides occurred, a dismal record unseen since the country’s civil war broke out in the 1980’s and that has positioned El Salvador as the second most violent country in the world, according to the United Nations Index.

Kaslow writes in her article, In El Salvador, a glimmer of hope for a stronger economy, “… gangs’ grip on enterprise, the government’s pervasive abuse of power to wield influence and make money, and the public’s apparent resignation to the problems does not create much room for entrepreneurial spirit.”

These high levels of violence portend bleak economic opportunities for the country of El Salvador.